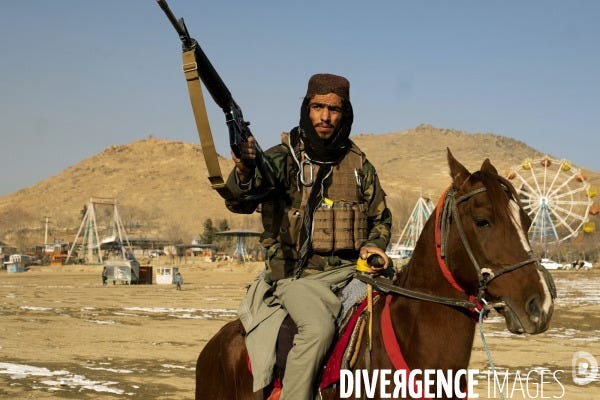

Image of Taliban fighter from Divergence-Images

Series intro:

The term “settler-colonialism” and its associated academic disciplines were designed to incriminate Israel and Anglophone ex-colonies like the USA, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. But the term would be better applied to Arab, Turkic, Persian, and other Islamic empires that colonized the world from Iberia to the Philippines and from Sarajevo to the Zambezi watershed. Present day threats to humans are far more likely to come from would-be Islamist colonial masters than from the usual targets of settler-colonial theory.

The leaders and citizens of not-yet-Muslim-majority nations often display basic misunderstandings about the past, present, and future of Islamic colonization. I hope this series sheds light on the matter.

In part 1, I discussed why I am using the term “settler-colonialism” despite its usual deployment in bad faith.

The Sages, the Redeemer, and the Prophet-Warleader-Lawgiver-Judge

The major Abrahamic religious civilizations took different approaches to political and military power. A brief look at their history will make it apparent that Islam’s approach to religio-political unity stems from the circumstances of its founding.

Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are inextricably linked due to shared history, shared scriptural narratives, and (as a result) long-term mimetic rivalry. Yet their foundations are different, as can be seen by considering what sort of men laid them. If we go back to the Hebrew religion that predated Judaism and figures strongly in the Tanakh,1 distinctions are made between priests, prophets, and kings. Priests upheld the sacrificial rituals prescribed by the Law. Kings led the politics, wars, and so on. And prophets arose from time to time to call them into check, or warn of destruction if people didn’t fulfill the spirit of the Law. While this system ended when the Romans destroyed Herod’s temple in 70 CE, there was a clear distinction between temple and throne though it had exceptions like the Hasmonean dynasty that followed the Maccabean revolt.2

The rise of Judaism from the sect of Pharisees following the destruction of the temple focused Jews on how to fulfill the Law in a world where they lacked political dominance. Scholarship came to be prized above hereditary priesthood.

After the disastrous Bar Kokhba rebellion in 135 CE, the vast majority of Jews in Judea and Samaria were slaughtered by the Romans.3 For the next 1800 years, the founders celebrated by Judaism were the Sages of the Talmud, not people of secular political power or military might.

The debates and conclusions recorded in the Talmud include “liberal” ideas like why they would never resort to capital punishment as well as “conservative” ideas such as complicating the rules for ritual dietary cleanliness. Even today, the extremist version of rabbinic piety, as held by haredi (AKA ultra-orthodox) Jews, forbids them from fighting for a secular government — a position that puts them at odds with the majority of Israeli society.

Jesus, on the other hand, began as a rabbi and faith healer of the Pharisee persuasion but came to be seen by his followers as God incarnate,4 sacrificial offering, redeemer, and future ruler of the world.5 For our interests, the political and military engagement of Jesus and the early Christians is wholly absent, conveniently “kicked down the road” to Jesus’ future return in glory and power.

Much ink has been spilled about the minority status of early Christians in the Roman empire and the numerous martyrs who were executed for their faith (and are still venerated as saints in the Catholic and Orthodox Churches). The Christian understanding is that both Jesus and his followers were made of the “suffering servant”6 mold.

That all changed when Emperor Constantine made Christianity the state religion. Bishops became politically powerful, and the cross and sword traveled together. The Roman settler-colonial project became a Christian settler-colonial project. Depending on how you define it, this state persisted through late antiquity and the middle ages, even into the nineteenth century if you count the Spanish and Portuguese conquest of the Americas.7

In the early part of this era of “imperial missions” Christian emperors and kings waged wars of expansion throughout Eurasia, subjugating pagans and converting them en masse to the Trinitarian religion. In the 15th century and following, Catholic friars blessed the conquest of Central and South America and assimilated the Indigenous Americans by converting them to Christianity. Yet even during this time, the power of church and crown were not always united, but rather played off of and occasionally opposed each other.

In the Protestant mercantilist empires of the 17th century and following, the ties became even looser. Protestant missionaries “felt the call” to proselytize “natives” in the colonies of their Euro-American powers, and they were welcomed by said colonial governments, but the primary outcome of this was secularization and/or highly syncretic new flavors of Christianity. Today, the vast majority of those former colonies have decolonized at the governmental level. Though similarly despised by the academic class, few of the later mercantilist colonies of Protestant Europe or Catholic France were settler-colonies.

From the start, Islam was different. Following the chaos of the Red Sea Wars between Jewish kings of Yemen and Christian kings of Ethiopia, the founder of Islam saw the need for a new politico-religious community that would supersede and assimilate the two prior Abrahamic religious communities.

His role was not merely that of an interpreter of God’s law, like the Jewish sages, nor a suffering martyr in some cosmic redemption effort like Jesus. Muhammad’s claim to fame included the main types of religious and political leadership, embodied in one person who came to be upheld as “the perfect man” by his followers, while not claiming to be divine.

Thus, Muhammad was a prophet, getting downloads of revelation from God as delivered by the angel Gabriel. Muhammad took on a role akin to a priest, leading his followers on the “straight path” of submission to God and the proper forms of worship. Significantly for this discussion, Muhammad was also a warrior, conquering cities and tribes who rejected his message, subjecting them to plunder, taxation (jizya),8 and second-class (dhimmi) status unless they joined his movement of the faithful. He was often referred to as a judge, one who settled legal disputes between the faithful.

That is to say, the apostle of Islam was not only theologically but politically remarkable. It took a while for Judaism and Christianity to combine secular and spiritual power in one person, and those experiments tended to prove short-lived. While later Muslim empires saw some distance between mosque and throne, the ideal state that Muslim would-be reformers hearken back to is the perfect man, leading the faithful of the perfect society as prophet, warleader, lawgiver, and judge. To use a current phrasing: In the ideal Muslim society, politics is downstream of religion.

Equally important were the rules prohibiting Muslims from converting to another religion. As Nassim Nicholas Taleb points out in a fascinating chapter of Skin in the Game, making conversion a “one-way street” creates a mathematical asymmetry that practically guarantees a society ruled by sharia9 will increasingly shrink its non-Muslim population.

The two asymmetric rules were are as follows. First, if a non Muslim man under the rule of Islam marries a Muslim woman, he needs to convert to Islam –and if either parents of a child happens to be Muslim, the child will be Muslim[3]. Second, becoming Muslim is irreversible, as apostasy is the heaviest crime under the religion, sanctioned by the death penalty. The famous Egyptian actor Omar Sharif, born Mikhael Demetri Shalhoub, was of Lebanese Christian origins. He converted to Islam to marry a famous Egyptian actress and had to change his name to an Arabic one. He later divorced, but did not revert to the faith of his ancestors.

Under these two asymmetric rules, one can do simple simulations and see how a small Islamic group occupying Christian (Coptic) Egypt can lead, over the centuries, to the Copts becoming a tiny minority. All one needs is a small rate of interfaith marriages.

Softened by time?

That said, origins are not everything. Religions change over time as human lifestyles, technology, and expectations evolve. At least that’s what one would expect.

Just look at the Vikings. They were colonizing Britain and Normandy for a good while, but now the states full of their descendants are seen as paragons of liberalism and non-aggression.10 All three of the great western religions discussed above have shown the capacity for change at varying points in their history. Nothing would last 1,400-2,000 years without adapting in some form.

Judaism emerged out of the wreckage of the ancient Hebrew religion, and has evolved into a multitude of forms today that range from humanism with Jewish trappings to ultra-orthodox interpretations of halacha11 (which are more of an attempt to freeze time in the 18th century than the 1st century CE, if we’re being honest).

While the modern state of Israel has engaged in warfare, this has been led by a secular government, and initiated for defensive reasons against Arab armies and militias who stated repeatedly that their goal was the total eradication of Jewish self-rule. The governmental structure of the modern state of Israel is something the sages of the Talmud could not foresee. And the conflict between secularists and “Torah-first” haredim is at the heart of Israel’s often chaotic democracy. Without a deeply inscribed theory of conquest and how to rule over subject peoples, the modern Jewish state is having to make it up out of whole cloth.

Christianity has gone from one big schism over innovations in the creed to fragmenting into thousands of movements and denominations, the most energetic of which are the newest — Evangelicalism and Pentecostalism. But even those old keepers of “traditional Christianity,” the Catholic and Orthodox churches, have innovated.

From supporting wars of conquest (as in the Reconquista of Iberia and subsequent conquest of the Americas) or inspiring and leading them (as in the Crusades), Christianity was no stranger to “holy war.” Indeed, following the Protestant Reformation, Christian Europe spent centuries soaked in blood, due to conflicts justified by a mix of political and religious exigencies.

This makes it all the more remarkable that, today, we see both “the Church” and churches largely eschewing religious violence and seeking to influence the world by means of moral sentiments and persuasion. The historically novel post-WWII era of widespread peace in Europe saw imperial expansion be supplanted by trade agreements and a vision of shared prosperity through international cooperation.

So why should we not assume that Islam will moderate and enter a new era of tolerance and international cooperation? Unfortunately, it seems that Islam is going the opposite direction.

The Islamic Superiority Complex, Confronted by Its Global Inferiority

The Islamic civilization in its caliphates, dynasties, and nations has cycled through varying degrees of prosperity, tolerance of minorities, and peace. There have been eras where trade around the Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean basin, and across the deserts of Arabia and North Africa was more important than conquest.12 But the great artistic and cultural achievements of Islamic civilization that we recognize in the west tended to coincide with eras the pious would regard as the most decadent and sinful. And while much has been made of the tolerance of Jews and Christians during the Convivencia period in Iberia or under the Ottomans, there were also extremist uprisings, like the al-Mohads in the former13 and unpredictable pogroms in the latter. Even though some “court Jews” were able to garner considerable influence, most of the Jewish merchants and artisans were keenly aware of their dhimmi status and could have their rights revoked at any time.

As Ayaan Hirsi Ali and other have pointed out,14 the glory days of Islamic superiority are stuck firmly in the past, in the time of the prophet and his friends. In recent years, satellite TV and now the Internet have enabled Muslims the world over to see the prosperity and (in their view) libertine lifestyles that people in western nations experience.

God promised that the faithful would be victorious. But wherever they look, the unfaithful, pagans, and atheists are dominating the world. Worst of all, the Levant is home to a Jewish state and a Christian-plurality state (Lebanon). The world of Dar al-Islam is never supposed to lose territory to Dar al-Harb.15 These examples of non-Muslim self-rule in Arab lands are a reminder of how far the Muslim community has fallen from its days of empire.

When people ask why Islam hasn’t had a reformation, I like to point out that it has had several.16 But reformation looks different in the Islamic context. When Muslim leaders think about reform and improvement, they are not looking to the future. Their prescription is to restore the old ways. Since Muhammad was the perfect man, then being more like him and ruling like him will perfect the world.

WWMD?

One of the most dramatic shifts in 20th-century geopolitics was the resurrection of political Islam. As the Ottoman empire was divided into Arab and Turkish nation-states, tribal power games that had been subjected to the Ottoman system came to the fore once again.17 Reformers like Hassan al-Banna, founder of the Muslim Brotherhood looked at the crisis of civilizational decline, and stated “Islam is the answer.” More piety, better adherence to the prophet’s role modeling, and restoring medieval ways of life would bring about the restoration of the glory days. However, unlike Independent Fundamentalist Baptists in the USA or ultra-orthodox Jews in Israel, their vision of struggle is not merely spiritual.

One irony of the last century or so is that both nationalist movements and Islamist politics (with a heavy dose of terrorism) have led to the homogenization of the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of South Asia. Raymond Ibrahim points out that Egypt was once a Christian-majority country. But while the Coptic Church lost its majority centuries ago,18 the 20th century campaigns waged against Armenians, Greeks, Jews, Kurds, and others have been swift and brutal.

As Nassim Nicholas Taleb states, the puritanical fervor of Muslim reformists has changed the facts on the ground.

Islam? there have been many Islams, the final accretion quite different from the earlier ones. For Islam itself is ending up being taken over (in the Sunni branch) by the purists simply because these were more intolerant than the rest: the Wahhabis, founders of Saudi Arabia, were the ones who destroyed the shrines, and to impose the maximally intolerant rule, in a manner that was later imitated by “ISIS” (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria/the Levant).19

Some of the oldest Christian communities in the world are in Syria. Yet Christians, Druze, Kurds, Mandeans, and Alawis may be at risk under the new Turkish-aligned Islamist government of Syria. Chaldean Christians and Yazidis certainly suffered under the government of Iraq after that country was “liberated” from Saddam Hussein’s Baath Party.

In 1947, there were over 900,000 Jews living in the Arab world and Iran, not including British Mandate Palestine. But as a result of pogroms and forced expulsions, hardly any Jews live in these countries today. Many of them made their way to Israel; others to Europe or the Americas.

The reverse is not true. Despite much anti-Israel publicity about the nakba, the modern state of Israel is made up of not just Jews, but also Muslims, Christians (of many varieties), Druze, and other minority groups. There are even a few thousand Lebanese Arab Christians who were granted citizenship in Israel for their role in fighting against Shiite militias (later replaced by Hezbollah) in the Lebanese civil war.

Looking further east, at the time of partition from India in 1947, Pakistan was 23% non-Muslim. Today, it is only 3% non-Muslim.

Today, North Africa and Turkey are about 97 percent Muslim — even though, along with Egypt and Syria, both regions once formed the heart of the Christian world. (St. Augustine, the father of Western Christian theology, hailed from modern-day Algeria; and Anatolia — “Turkey” — is the site of the oldest churches that received epistles from the apostles.)

In short, it is no exaggeration to say that “the Islamic world” would be a fraction of its size (and perhaps might not exist at all) were it not for the fact that more non-Muslims were pressured into self-purging their largely Christian identities to evade persecution than those who were physically struck down by the sword.

This is classic settler-colonialism, but the proponents of settler-colonial theory would say anyone who makes that claim is Islamophobic. As I have said elsewhere, phobias are irrational fears. If your fear has a rational basis, it’s not a phobia.

In this piece, I’ve focused mostly on the greater MENA region. But what does all this mean for not-yet-Muslim-majority countries dealing with growing Muslim populations who resist integration to local norms? I will turn to that in the next installment of this series.

To be continued in part 3, The Clash of Civilizations I Didn’t Want to Believe In…

AKA the “Old Testament” to Christians or “Tawrat” and “Zabur” (Torah [Book of Moses] and Psalms [Book of David]) to Muslims

In older examples of the separation between kings and priests, Israel’s most famous king, David, was prohibited by divine decree from building the first temple because he was a man of war. And King Uzziah was cursed with leprosy for presuming to burn incense in the temple — a duty reserved only for hereditary priests.

This led to the myth of permanent exile that was celebrated by Christian theologians and endured by generations of Jews. Nonetheless there has been a continuous Jewish presence in the land (if at times small) for around 5,000 years.

A shockingly effective fusion of Greco-Roman and Jewish concepts of divinity

The Apostle Paul, an itinerant preacher and miracle worker, is credited with much of the rebranding effort here.

This expression comes from a Christian appropriation of Isaiah 53 to apply to Jesus, when it was originally meant to describe the collective sufferings of Israel.

The Mexican Inquisition, an agent of cultural assimilation, wasn’t disbanded until 1820.

For more info on recent application of jizya - https://www.forbes.com/sites/kellyphillipserb/2014/07/19/islamic-state-warns-christians-convert-pay-tax-leave-or-die/ and https://www.churchinneed.org/mali-jihadist-group-intensifies-religious-persecution-and-charges-christians-jizya-tax/ and https://www.meforum.org/jizya-the-return-of-muslim-extortion

Note also that the primary argument in defense of taxing non-Muslims is that they are not being conscripted to fight — meaning only Muslims can fight for the Islamic society, and thus underscoring the lack of real pluralism.

This is in stark contrast to the Zionist state of Israel, where Druze, Muslim, and Christian Arabs are able to serve in the IDF if they desire to, though they are not required to like most Jewish citizens. There is currently a heated debate over attempting to force Haredi (AKA Ultra-Orthodox) Jews to serve in the IDF, as they had been given an exemption in exchange for their toleration of the secular government.

Islamic law, as derived from the Qur’an, Hadith, and centuries of religious jurisprudence

One could have a lively discussion of the role of Christian colonization in pacifying the Vikings, but that’s outside the scope of this article.

Jewish ritual law, the subject of the Talmud — expected to be observed by Orthodox and Ultra-Orthodox Jews

Though let’s not forget that trade in slaves was as much a part of Islamic civilization as any western civilization, and indeed was legal for far longer — until 1960 in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, for instance.

Responsible for a young Maimonides’ flight from Spain to North Africa, and eventually Cairo

For instance, in Hirsi Ali’s book Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation Now

"Lands of Islam”…”Lands of War” (AKA any non-Muslim ruled lands)

The American Muslim scholar Jonathan A. C. Brown also makes this point in his book Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Intepreting the Prophet’s Legacy (2014), although his partisan leanings are different than my own.

For instance, the House of Saud and the Hashemite kings of Jordan both claim genealogical descent from Muhammad. Giving each their own kingdom was part of how Britain attempted to keep the peace.

In contrast to Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s account mentioned above, Raymond Ibrahim argues that persecution was a bigger factor than mere personal gain for Egyptian Copts considering conversion to Islam. https://www.meforum.org/the-drip-drip-genocide-of-christians-in-muslim

While Taleb (perhaps remembering the happier parts of his childhood in Lebanon) gives Shia Muslims a pass, the existence of Hezbollah, the Houthis (who restored slavery to Yemen), and the brutally repressive Islamic Republic of Iran does little to commend that variant of Islam as more tolerant or less expansionist. And let’s not forget the Shia leadership of Iraq, which just lowered the legal age of marriage for girls to nine years old, because that was the age of the prophet’s favorite wife when he married her.

Fascinating article. Some minor points:

In terms of conversion to Islam, it’s historically often been pushed by more than just intermarriage and even persecution. Given that Muslims have many privileges over non-Muslims in Islamic states, including tax exemptions and potential career advancement, it’s not surprising that many non-Muslims have willingly converted after conquest. I think a similar trend has been seen in some Medieval Christian societies where the aristocracy converted first – it becomes prestigious and rewarding to convert.

Interestingly, the early generations of Muslim leaders were in no hurry to encourage conquered peoples to convert (despite Islamic law recommending it), preferring to keep their privileges and the exclusive nature of Muslim status. This didn’t last, though.

Slavery basically does *still* exist in parts of the Arab world, notably Qatar and Yemen.

A slightly tangential point, but you talk about the claim that Islam needs a “Reformation.” This may be semantics, but I’d argue it actually needs an “Enlightenment.” The Reformation was mainly about the role and authority of the papacy, indulgences and the nature of the mass (transubstantiation and also who gets to partake of what). As you say, it led to over a century of bitter religious warfare.

The “liberalizing” of Christianity and Judaism took place as a result of coming into contact with the Enlightenment (which they often initially resisted), ultimately producing more liberal churches, Progressive Judaism and Modern Orthodox Judaism. The decline of many of these and return to more fundamentalist values makes me doubt that anything like this could happen to Islam soon (some more liberal Gulf States not withstanding).

Good point about Islamophobia.

Excellent piece. I don’t think Christianity is solely “Western” even though it is mostly now. Also, I think the diverging paths of the 3 Abrahamic faiths were contingent on their philosophies, ie. both Christianity and Islam were convinced they were better than Judaism and spread their ideas to whoever would accept them - as opposed to the Jews, for whom their spirituality was and is part of their core identity as a people, not simply a religious ideology that anyone could adopt easily. Jews don’t prosthelytize, and besides, it’s harder to spread your ideology when it’s tied to being part of a particular society. I also question Islamic/Arabic claims to being decendents of Ishmael. What proof of lineage do they have? I’d like to see that, if anyone can share something. The only thing I’ve ever seen is that Israelite kings sometimes hired (pre-Islam) Arab freelance warriors for their archery skills - something Ishmael was famous for. The only reason I care about that is because of Islamic usurping of Jewish history that allows them to do things like build a mosque on the Tomb of the Patriarchs.